In 1968, when my mum was nine years old, her house on Dharug country/Blaxland burnt down. Months of punishingly dry weather, with no land management to speak of, had left the Blue Mountains teetering on the brink of catastrophic fire. Inevitably, some miserable ember caught hold. She managed to take a few things with her — some school books, a pieces of clothing, a photo album. Those scattered objects aside, all that remained was the brick fireplace.

It is hard to resist constructing my own version of that house in my imagination. I never met my grandparents, and I’ll never read their correspondence, or glance into a cabinet of strange sepia photos or kitsch porcelain, or inhale the deadening assault of cigarette smoke, that I know for a fact would have haunted those rooms like a crude poltergeist, and the cold brick intersecting with dank carpet (though cosy and invaluable) and the vaguely acidic smell attached to wood and vinyl, the mild hint of the eucalyptus, frying gently in its own sun-soaked oils, just beyond the windows. The myth making is gratifying, in order to reconstruct some aspect of a lost family archive. A treat of memory forgery. Art-making often grapples with these voids, attempting to gather the dust of the self, and the dust of those networked to us. In the absence of an archive, of something legible and tangible, the act of making must serve as the catalyst for storytelling. It is existence speaking back, echoing a feedback loop through texture and temperature. It is evidence through time, of persistence, and of traces of purpose and intention. While romanticising the past is a precarious action, its tangible heirlooms offer a kind of medium for self-interpretation, and a catalyst for self-construction. Encountering these kinds of art objects sends me, not backward, but rather outward through time, into the “could’ve” rather than “was”.

It is unsurprising then, that when I see objects that articulately capture this “grappling”, I’m enamoured. I return often to the work of Australian artist Drew Connor Holland in particular. His practice is varied in media and method, but with a recursive, key attribute — gathering up personal detritus, melting it down, and rematerialising it in new forms imbued with new meaning — the “could’ve” coming into view. His early work sees this aspect of his practice expressed in the making of homemade paper. Holland’s paper making process is bold and widely encompassing — constructed from a plethora of printed ephemera from Holland’s day-today life, one will find receipts, pamphlets, exhibition catalogues, 3D glasses, gifted artworks, discarded sketches, pieces of clothing, pieces of quilt, and his mother’s own hair. Onto this paper he makes solvent prints of warped digital avatars, some made in the 2000s/2010s online 3D life-sim(ulation)

Second Life, and others later in wrestling videogame WWE2K (the 2019 & 2020 versions, I believe). These digital avatars give Holland a broad palette with which to illustrate his own body, that body amongst others, dissociative bodies, meshings of limbs, and play with the mythology of the portrait — the “projected self”, the “self as image” and “as object”, and all the curiously inauthentic and authentic aspects that make up what we can then know as “the artist”. But it is materiality that binds the spell. These discarded day-to-day fragments, arguably unimportant, become the most essential — they make the paper, indeed the body of the object, real.

Drew Connor Holland

(One foot over the other – cross-legged as I lay cold) (2016 – 2018)

Solvent print on hand-made paper

These newly essential things, suddenly loaded with personal value, take on sentimental and delicate qualities. (One foot over the other: cross-legged as I lay cold) (2016-2018) shows the fragmented torso of Holland’s Second Life avatar, clad in a cheerfully pink and white lace cowboy hat. It floats aloft two other figures, they too fragmented and seemingly melting into (or out of?) the foggy, humid haze of colour — possibly a backdrop of a tropical digital setting, though the details dissolve any chance of specificity. Bones, or perhaps branches, intersect which Holland’s godly central presence, and squashed secondary faces also peek out from where the avatar’s chest should be, like a divine chimera. The image appears like a hypnogogic flash, something uncanny one might glimpse momentarily when pivoting in a dream. The “manipulated screenshots” are printed onto paper made from “misc items (trash), drawings, charcoal, human hair, bedsheets, shirt, denim”. The materiality, like the imagery, is chimera-like — fragments reassembled into an object that creates an affectual power that this detritus separately is unlikely to conduct. These images behave like nostalgic memories — fragmented but warm, unreal but born of a prying self-reflection, nonrepresentational but authentically emotional. I see methodologies of my own mind echoed back at me.

Drew Connor Holland

Poems v (2023)

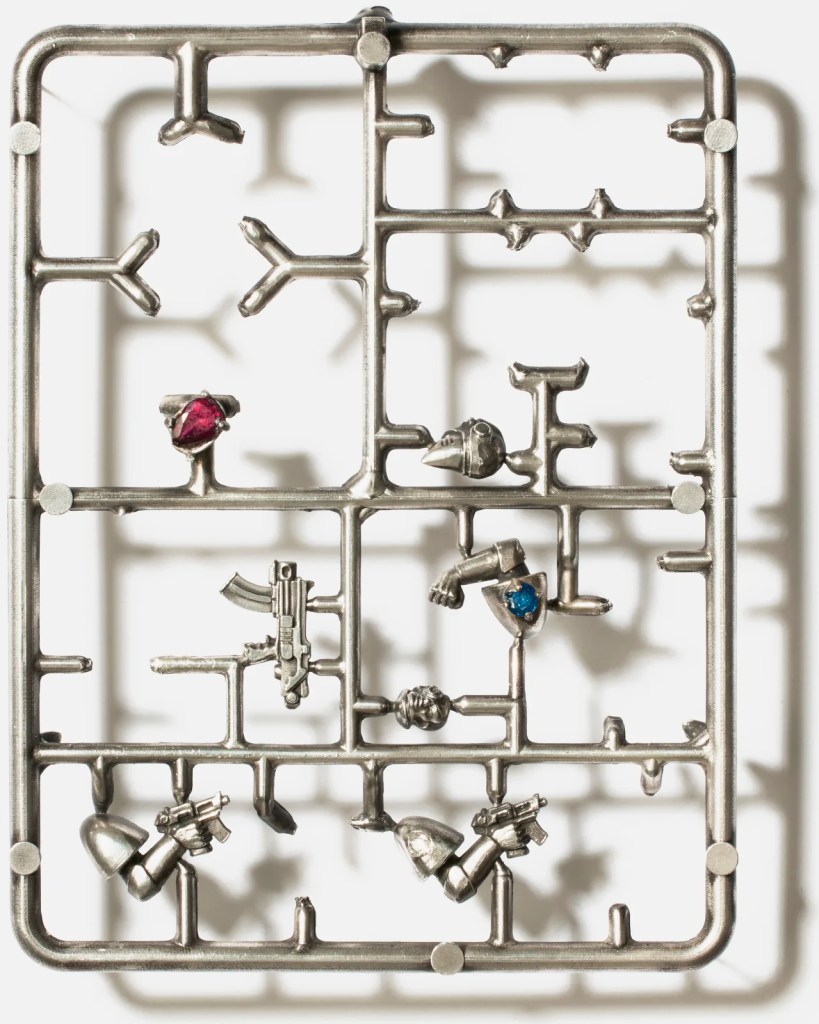

Silver, London blue topaz, pigeon blood ruby 11.7 x 8.5 cm

Increasing the potency of this approach further still is Holland’s series Poems (i-v) (2023). These are five cast silver sculptural pieces, studded with gems. For those unfamiliar with the visual reference from the outset, a viewer may see these works as resembling an industrial spider-web, dotted with prone, armoured limbs clutching weapons as though from a body dismembered and randomly strewn, and studded with glassy gemstones. They hang like souls haunting the fragments of their former bodies. But Holland’s story for the works, and their complex sentimental value, reveals how their form and materiality reconstitute the past and the present into affirmation of one’s own legacy. Holland details that these webs are in fact, “sprues”, the (originally plastic) frames that contained body parts for the collectable hobby figurines Warhammer 40,000, miniature statuettes to be extracted, and meticulously glued together and painted.

The sprues used here specifically, according to Holland, are of the “RTBo1 sprue (that) was released in 1987, the first multi-part customisable Space Marine kit that launched the Warhammer 40,000 range … These remnants, essentially worthless, held decades of sentimentality to their owner.” His statement is worth quoting in full — as a summary of a story is not really as much of a story: “My grandfather, by no means a good man or a sound investor, would give me silver coins on my birthday. The intention was for them to accrue value as an asset; a solid silver Melbourne Commonwealth Games commemorative coin was of no interest to me as a boy and its only use was to act as this shallow placeholder for luxury with no ontological value. I had the silver coin — a kilogram of metal which constituted a lesser $100 in legal tender — melted and cast into the used sprues and studded with gifted gems. These works function as intermediaries between two values: treasured garbage and trashy treasure. The pieces were oxidised and polished; the finish resembling an old goblet or collectible spoon. The space between the arms and the legs that built toy soldiers gives space for crystals to grow. These works try to synchronise a precious memory; a new thing feels like something ancient and cherished.”

A part of me is suspect of Holland’s story — it’s almost too emotionally aligned and materially serendipitous to unfurl so naturally. Though isn’t that the magic of a mythology? Truth and memory and narrative intertwine to elicit an inclination to lean forwards, pulled by some unnamed emotional flutter, to say “and then what?” and “tell me more…” Here, contrivance is not a pejorative, but an essential ingredient in the recipe of the auto-biography. The pages are dirty silver, and the words are swooning nostalgia. It is a more truthful personal artefact than the incidental gift or forced acquisition — made real through its fakeness. It is evidence of Holland’s passions, waiting to be gently excavated out in some deep future scenario, in which we are all buried under our dust and our plastic and our junk.

Years ago, I gave my mum a sketchbook-journal. A truly kitsch and unnecessary object. I had imagined that perhaps this journal, with its daily prompts to draw, no matter how simple, would be a means to acquire a permanent artefact of her for my own future. But you cannot force rituals on those who are not already seeking them. You cannot make someone who does not inherently draw, or journal, or otherwise make, do so. And so, after a few days of humouring my (in retrospect, somewhat selfish) gift, she placed the journal in a drawer of desk and forgot about it. Not through any kind of malevolence or apathy. It was just not to be. I’d given her a pile of silver coins. My mistake was attempting to delegate the memory making. Mum has already made her artefacts, and she lives in and amongst them. I doubted my capacity to make my own, despite having unknowingly laid the groundwork for them. I need to go build a house in the mountains out of half-a-dozen half- filled sketchbooks, iphone glass, ten years of chest hair, shattered ceramic mugs, gavascon boxes and gargantuan blister packs, gallery room sheets, two dead hard-drives, Jatz, washi-tape fragments, diy lubricant polymer dust, browned palm fronds, torn shirts, birthday cards, hdmi cables, a single arm from sticky silicon tortoise-shell eye-glasses …

Originally published in Pang, 2025.

Leave a comment